I'm going to throw you part of something I've been working on, about the very early days of the Greenwich St El.

What interested me about this subject is that so little is documented on the state of the first elevated line in Greenwich St and Ninth Ave before its reconstruction in 1879 and 1880. I felt like I could add something. Some dedicated amateur historians, like George Horn of the Electric Railroaders' Association, pulled together information from company documents that were still available in the 1930s and onward. But not much had been kept about the old road, since there was no practical value to it after 1880. The increasing availability of full-text searching of newspapers and journals has now made it possible to gather bits and pieces of evidence that would have been nearly impossible to find previously.

I've written about this before. My excuse is that some of this is new.

When it first opened, the Greenwich St El was operated by cable power. The man behind the project, Charles T Harvey, wanted to avoid using steam locomotives, because of the soot and smoke, the noise, and the danger from boilers exploding. His contemporary, Alfred E Beach, proposed using pneumatic pressure in tubes, and built a demonstration one-block subway in 1870. Harvey proposed a system with moving cable that the cars could grab to carry them down an elevated track. Both systems still involved stationary steam engines located in buildings along the way to supply the pneumatic or cable power. The ultimate solution to the problem, electric motors, were not practical until about 1885.

Harvey built a first segment one block long in October and November 1867. The track was supported by a line of columns along the east curb line of Greenwich St from Battery Place to Morris St. He was able to run a handcar by cable power on December 7, gaining approval to build a further segment up to Cortlandt St.

The second segment was built in March and April 1868. What newspapers called a "trial car" was placed on the structure about May 1, and Harvey gave it a test run for the state-appointed commissioners on June 6.

Here is Harvey demonstrating cable power on December 7, 1867. He is riding a handcar, which would normally be moved by trackworkers turning the handles of the flywheel behind him. But instead Harvey is sitting holding a rope like the reins of a horsewagon, which is evidently attached to the cable. The cross street there is Morris St, so the structure ended just off frame on the left. One of the men in the crowd would continue working on the elevated lines into the 20th century.

Here is the "trial car" at the Cortlandt St end of the second segment, some time between May 1868 and the start of further construction in 1869. The beams are very thin, with a slightly heavier one across Liberty St. The "track" consisted of flat iron strips laid over a cushioning material laid directly on the beams.

The main line up to 30th St was built during 1869 and 1870. The columns, made by the company at its factory in Harrison St, were placed at the east curb line of Greenwich St and the west curb line of Ninth Ave, crossing over at Gansevoort St. By November 1869 the structure was up to Canal St, and it was complete to 30th St by March 1870.

Cable cars are familiar today because of the surviving routes on the streets of San Francisco. An endless loop of cable runs from the powerhouse down to one end of the line, back up to the other end, and back into the powerhouse. The engine in the powerhouse moves the cable continuously throughout the service day. The cars have no power, but can grip the cable to move, or release it and brake to a stop.

The grips used in San Francisco were not yet invented in Harvey's day. His concept was instead to have little wheeled units he called travelers permanently affixed to the cable every 150 feet, with a "horn" projecting up. When the car was to move, the operator turned an iron wheel on the end platform, and a hook under the car would snag the next horn to come along. Turning the wheel back the other way would disconnect the hook.

Streetcar cables run at about 7 miles an hour, and the grip can be closed gradually so as to slip for a moment, bringing the car into motion and then to full speed as the grip is made tight. Harvey wanted to run the cable 10 to 15 miles an hour, and it would suddenly jump forward when the horn was snagged. Arrangements of springs were used on the hook and in the car body, but riders still reported a tremendous jolt when the car started.

This is a traveler.

The problems of the Harvey system, when it operated properly, were the least of it. There was a collision at 29th St terminal on June 14, when an arriving car would not detach from the cable, and it rammed another car, snapping the cable. Since the car overshot the platform and could not be moved, passengers had to go down to street level by ladder. On June 22, the machinery was smashed as a car crossed over the cable break at Houston Street, and a wheel (from a traveler?) fell in fragments to the street. Again the passengers had to escape by ladders. On some other occasions, when the cable failed, a rope was then attached to the front of the stalled car and the other end was thrown to the street where a truck with four horses, if they could make it, pulled the car.

The trade publication Iron Age ripped it apart:

... it is constructed with but little apparent regard for scientific or mechanical principles ... the motion is uneven and disagreeable, and the gradual loss of impetus in passing over the bridges between the sections [the cable gaps], necessitates a succession of sudden and unexpected jerks as the tracks attached to the cables come in contact with the spring affixed to the under part of the car. The worst feature of the road, however, is the weakness of the structure, sustained by single posts, and possessing no side braces or supports to overcome the lateral motion of the heavy cars balanced on the spreading arms that hold the tracks. These defects should have been discovered before a hundred feet of the road had been built, if not sooner ...

The cables were short compared to later street railways. There were four engine houses and nine cables, in a distance of only 3.3 miles.

CORTLANDT ST cable. This house was opened in 1868 and powered the demonstration sections south to Battery Place. (The temporary powerhouse for the first block in 1867 is unknown but was probably at Morris St.) This cable was built differently from the others because it returned in a vault under the sidewalk. It was noticed in early 1868 that water got into the vault, and freezing would interfere with cable operation. The main line was built with the cable returning directly under itself up on the structure. The Cortlandt St cable was not used in regular passenger service.

Cable gap at or near Cortlandt St, location not documented.

FRANKLIN ST south cable to Cortlandt St.

FRANKLIN ST north cable to Houston St.

Cable gap across Houston St.

BETHUNE ST south cable to Houston St.

BETHUNE ST north cable to Gansevoort St.

Cable gap across Gansevoort and Little W 12th Sts.

22ND ST south cable to Little W 12th St.

22ND ST north cable to 30th St.

Below is a typical section of the main line, at Fulton St. You can see the cable returning, below the beams and passing through a redesigned column. Again the beam across the street is a little heavier than the others, and it has truss rods too, possibly added as a result of the May 1870 load test.

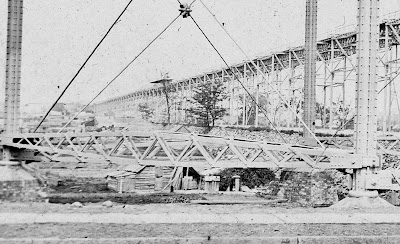

This is the cable gap between the end of the 22nd St south cable at Little W 12th St, foreground, and the Bethune St north cable at Gansevoort St, background. Cars had to coast across, losing speed as they went, until they were jolted back to cable speed at the other side. The big drums are where the cable loops back under itself to return to the powerhouse. This is also where the el crossed from the west curb of Ninth Ave to the east curb of Greenwich St.

This wonderful illustration shows that the 22nd St powerhouse was below street level at the northwest corner. On the left, a typical elevated column has been adapted to support the smokestack from the unseen stationary steam engine. There is only a small cable gap here between the south and north cables, so maybe less of a jolt.

Passenger service was operated from Dey St to 29th St. Dey St station was located at the southeast corner partially in the Exchange Bank building. 29th St station was located across 29th St with a stairway at the southwest corner. At both ends there was one block of cable past the stations, to Cortlandt St and 30th St respectively, which was used to set cars that were not in service. There were no sidings.

Dey St station, still under construction in 1869. The ticket office is built into the Exchange Bank building on the left. It's hard to be sure, but under the word "boots" on the sign may be the big drum at the end of this cable.

29th St station, 1870. The stationhouse is barely large enough for one person, and the platform is clearly no longer than one car.

Regular service started on June 11, 1870 (many sources give earlier dates), and ran intermittently because on many days the line was closed for repairs. By mid August the line was reported as no longer running. A "pneumatic engine", which was shaped like a small steam locomotive but ran on a tank of compressed air, was tried in September. The line reopened with cable power on November 14 but was closed for mechanical failure by the end of the day. And that was all.

The property was foreclosed and sold, and the new owners tried operating with a small steam engine in April 1871. But that's another story.